Stair Calculator Explained: Measurements, Code Requirements, and Common Errors

Hey there, fellow DIYers and weekend builders — if you've ever stared at a stair project wondering "did I just screw up my measurements?", you're in the right place.

I'm Hanks. I spend way too much time testing tools and workflows to figure out what actually works in real projects. And I spent way too long last spring rebuilding a set of deck stairs because I trusted my math without double-checking. The bottom riser came out half an inch taller than the rest. Half an inch. The inspector took one look and failed it on the spot. Two days of work, $200 in lumber, gone.

That's when I got serious about stair calculators. Not because I can't do math — I can. But because these things catch the stupid mistakes that happen when you're tired, or when you forget to account for that 1.5-inch deck board thickness, or when you round 7⅝ to 7.5 instead of 7.625.

So here's what I've learned after running dozens of stair projects through calculators, making mistakes, fixing them, and figuring out what actually matters.

What the Stair Calculator Does

A stair calculator takes your basic measurements and calculates the precise dimensions for every step in your staircase. Think of it as your math partner that prevents the kind of errors that'll bite you during inspection.

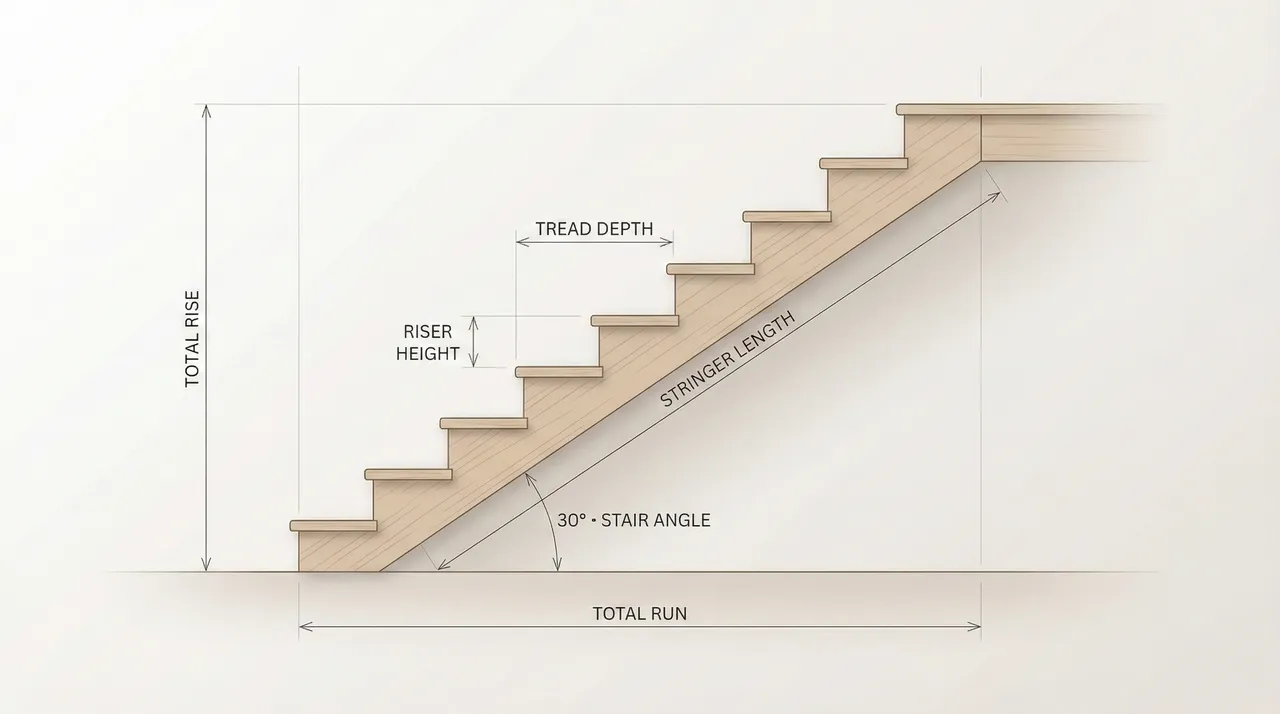

Calculations Provided

When you plug numbers into a quality stair calculator, you get:

- Number of steps (risers) — The calculator divides your total rise by your target riser height, then rounds to get whole steps

- Rise per step — Your total rise divided by the number of steps (this needs to be consistent)

- Run per step — The horizontal depth of each tread where your foot lands

- Total run — The complete horizontal distance your stairs will cover

- Stringer length — The diagonal measurement you'll use to cut your support boards

- Stair angle — Usually between 30° and 37° for comfortable climbing

Most modern calculators give you two calculation modes:

Use One Run — You specify the horizontal depth per step (like 10 inches), and the calculator figures out your total horizontal distance.

Use Total Run — You specify the total horizontal space you have available (like 120 inches), and the calculator divides it evenly across your steps.

I prefer starting with "One Run" mode because it lets me design for comfort first, then check if it fits my space. If it doesn't fit, I switch to "Total Run" and see what compromises I need to make.

The calculators that also check your dimensions against the 2024 International Residential Code (IRC) are worth their weight in gold. They'll flag violations before you make the first cut.

Who Needs This

Honestly? Anyone building stairs. I use these calculators for:

- Deck stairs — Where outdoor conditions and finished deck height create unique challenges

- Interior remodels — When you're working with fixed ceiling heights and existing floor levels

- Small porch projects — Even a few steps need proper calculations to stay safe

- Code verification — Double-checking that your design meets local requirements

The calculator doesn't replace understanding building codes, but it makes compliance way easier to achieve.

Required Measurements

Let me break down what you actually need to measure. Miss any of these, and your calculator output will be garbage.

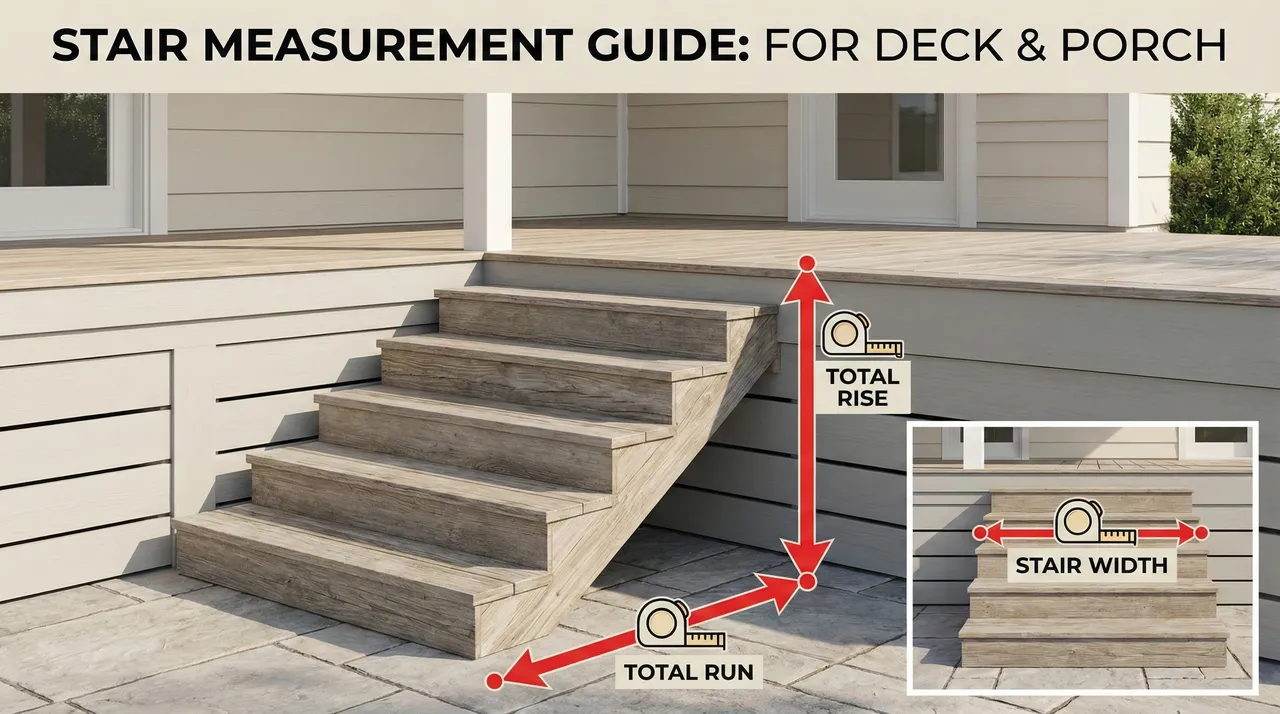

Total Rise

This is the full vertical distance from your lower finished floor to your upper finished floor. Not the subfloor, not the framing — the finished surface.

I learned this the hard way on my first deck project. I measured to the framing, forgot about the 1.5-inch decking thickness, and ended up with a bottom step that was off. Had to rebuild the whole bottom section.

Here's how I measure now:

Total Rise = Upper Finished Floor Height - Lower Finished Floor Height

For a deck that's 96 inches above grade with a 6-inch concrete pad at the bottom, your total rise is 90 inches (96 - 6 = 90).

Pro tip: If you're using the calculator's "automatic rise" option, it'll suggest the optimal number of steps. If you want to lock in a specific rise height (like 7 inches exactly), use the "fixed rise" option. And if you're matching an existing structure with a set number of steps, use "fixed number of steps."

Total Run

The horizontal distance your stairs will travel. Most calculators let you approach this two ways:

One Run mode — You specify how deep each step should be (the run per step). The calculator multiplies this by your number of steps to show you the total horizontal space you'll need.

Total Run mode — You tell the calculator how much horizontal space you have, and it divides that space evenly across all your steps.

I usually start with One Run mode because I can design for comfort first (10.5-inch treads feel good), then check if it fits. If my total run comes out to 140 inches but I only have 120 inches of space, I switch to Total Run mode and see what tread depth I end up with.

Stair Width

According to the International Code Council standards, residential stairs must be at least 36 inches wide, measured clear of handrails. Commercial stairs follow the International Building Code (IBC) with a minimum of 44 inches.

I typically design for 42 inches on residential projects. Gives you room for moving furniture and feels more comfortable.

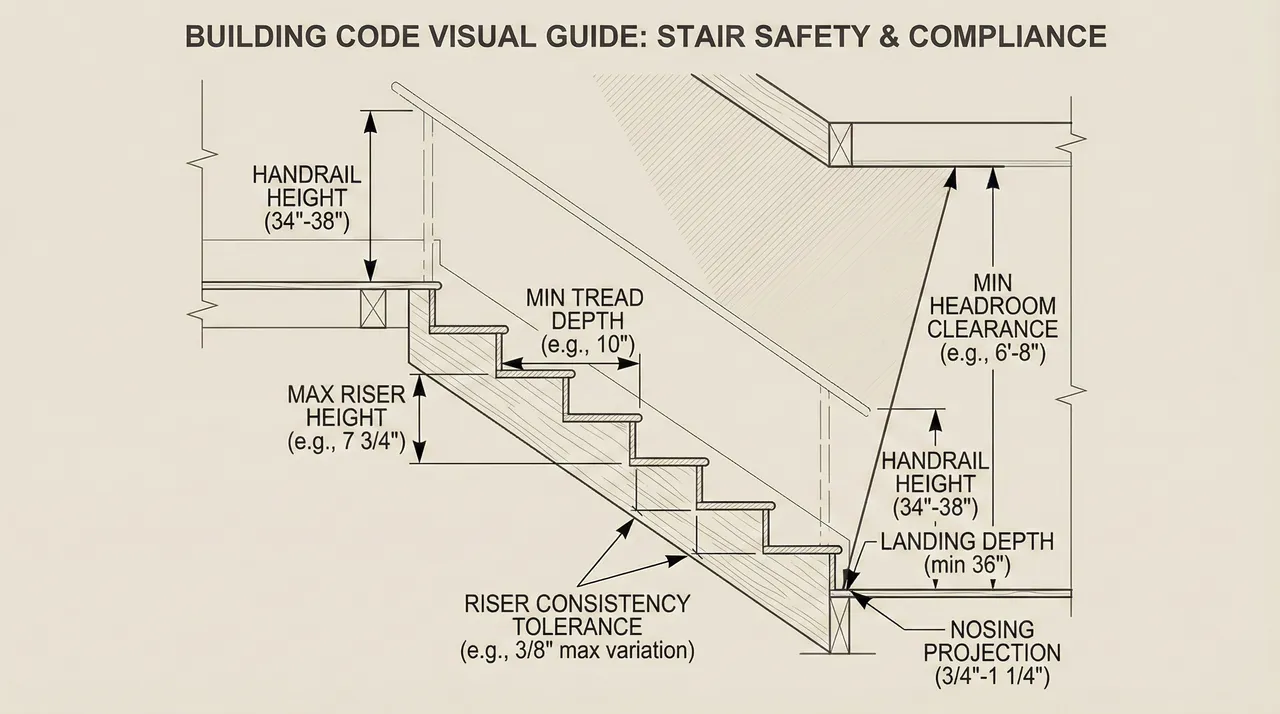

Building Code Basics

This is where most DIY projects go sideways. The 2024 IRC has specific requirements, and inspectors will check every one of them.

Riser Height Limits

The 2024 IRC sets the maximum riser height at 7¾ inches (197 mm). But here's what most people miss: the variation between risers in a single flight can't exceed ⅜ inch (9.5 mm).

That consistency requirement is where calculators really shine. They distribute your total rise evenly across all steps.

Some jurisdictions still use older codes with 8-inch or even 8¼-inch maximum risers. Always check your local amendments to the IRC.

Tread Depth Requirements

Treads must be at least 10 inches deep (254 mm) when measured from the leading edge of one tread to the leading edge of the next. If you're not using nosing (the part that overhangs), you need 11 inches minimum.

I've seen builders try to squeeze stairs into tight spaces by cutting tread depth. Don't do it. Shallow treads are dangerous and won't pass inspection.

The variation rule applies here too: the difference between your largest and smallest tread can't exceed ⅜ inch.

Headroom Clearance

You need 6 feet 8 inches (80 inches) of clear headroom measured vertically from the tread nosing line to any overhead obstruction.

I once miscalculated headroom on a basement stair project. Had to lower the entire ceiling to make it work. That's an expensive mistake that a proper stair calculator would have flagged immediately.

Common Calculation Errors

Let me walk you through the mistakes I see most often — and how to avoid them.

Measurement Mistakes

Forgetting finish materials — This is probably error number one. You measure to raw framing, but your finished floor will be 1-2 inches higher with decking, tile, or hardwood.

Fix: Always add finish material thickness to your measurements before using the calculator.

Measuring from wrong reference points — I've watched people measure from the top of the rim joist instead of the actual deck surface.

Fix: Mark your finished floor heights clearly and measure between those exact points.

Rounding errors — Some calculators accept fractions, others want decimals. Converting 7⅝ inches incorrectly to 7.5 inches instead of 7.625 inches throws everything off.

Fix: Use a calculator that accepts both formats, or convert carefully. That ⅛-inch error multiplied across 13 steps becomes significant.

Code Violations

Here's what gets flagged during inspections:

Inconsistent riser heights — When the bottom or top riser differs from the others by more than ⅜ inch. Usually happens when you don't account for finish materials.

Treads too shallow — Trying to fit stairs into limited space by reducing tread depth below 10 inches.

Missing the 2R + T comfort formula — This isn't always code, but it's good practice. The formula 2 × Rise + Tread = 24-25 inches creates comfortable stairs. For a 7-inch rise and 11-inch tread: 2(7) + 11 = 25 inches — right in the sweet spot.

Open riser violations — If you use open risers (no vertical board between treads), the opening can't allow a 4-inch sphere to pass through. This is a child safety requirement.

Pro Tips

After running calculations for dozens of stair projects, here's what actually matters.

Safety Margins

I always build in a little cushion:

- Target riser height: 7 inches — This gives you room below the 7¾-inch maximum

- Target tread depth: 10½ inches — More comfortable than the 10-inch minimum

- Stair angle: 33-35° — Falls in the comfortable range and passes code easily

The 2R + T formula I mentioned earlier? That's your comfort check. If your calculation gives you 2(7.5) + 10 = 25 inches, you're golden.

Material Considerations

Different materials affect your calculations:

Pressure-treated lumber — Standard for outdoor stairs. I use 2×12 stringers for most residential projects. The uncut portion of the stringer needs to be at least 5 inches high for structural integrity.

Composite decking — Can span farther than wood on flooring but requires closer spacing as stair treads due to the concentrated load requirement (300 lbs per 4 square inches).

Stone or concrete treads — Heavier and often require steel or aluminum stringers for long runs.

The calculator will give you a stringer length, but you need to add a few inches for cutting and fitting. For a calculated 142-inch stringer, I buy a 12-foot (144-inch) 2×12.

FAQ

Q: How do I calculate the number of steps I need?

Divide your total rise by your target riser height (I use 7 inches), then round up to get whole steps. So for a 90-inch rise: 90 ÷ 7 = 12.86, round up to 13 risers. Your actual riser height becomes 90 ÷ 13 = 6.92 inches.

Q: Can I use different riser heights to make stairs fit my space?

No. Building codes require consistent riser heights within ⅜ inch of each other throughout the entire flight. You need to adjust the number of steps or your total run, not individual risers.

Q: What if my calculator shows a code violation?

Common fixes: add one more step to reduce riser height, increase your total run to allow deeper treads, or add a mid-flight landing if your total rise exceeds 151 inches (the IRC maximum between landings).

Q: Do outdoor stairs have different requirements?

Same dimensional requirements, but you need pressure-treated or naturally rot-resistant materials, proper drainage so water doesn't accumulate on treads, and consideration for freeze-thaw cycles in your foundation/footings.

Q: How do I handle the bottom step when building deck stairs?

The first step height (from ground to first tread) must match your calculated riser height. If you're landing on a concrete pad, measure from the pad surface. If you're landing on grade, you might need to pour a small landing pad or use a precast concrete block to create a level, stable surface.

Putting It All Together

Look, stair calculators remove the math headaches from stair building, but they can't fix bad input data. Measure your total rise carefully, account for all finish materials, pick your calculation mode (One Run vs Total Run), and understand the code requirements before you start cutting.

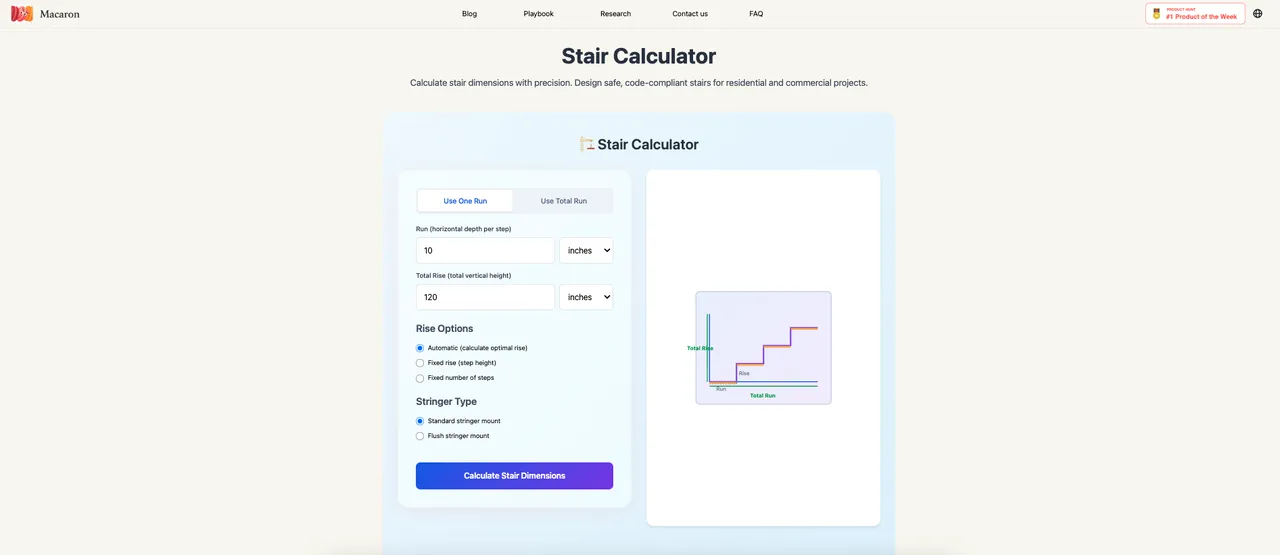

I've been running these calculations through macaron.im's stair calculator for my recent projects. Here's what I actually use it for:

The calculation modes matter — When I'm designing for comfort, I use "One Run" mode and set my preferred 10.5-inch tread depth. The calculator shows me the total horizontal space I'll need. If that doesn't fit my available space, I switch to "Total Run" mode, enter my actual space constraint, and see what tread depth I end up with.

Rise options are flexible — I can let it auto-calculate the optimal rise, or lock in a specific rise height (usually 7 inches), or even specify exactly how many steps I want if I'm matching an existing structure.

Stringer type selection — The Standard vs Flush mount toggle changes how the calculator handles your bottom step and stringer attachment. I use Standard mount for most deck stairs (treads sit on top of stringers), but Flush mount when I want a cleaner look on interior stairs.

Code compliance checking — This is the feature that's saved me from do-overs. The calculator flags violations automatically. If my riser exceeds 7¾ inches or my tread drops below 10 inches, I see warnings before I cut anything.

The calculator is free to use, handles both metric and imperial units, and shows you a visual diagram of your stair layout. You can save your calculations to reference during the build, which beats keeping track of scribbled notes.

If you're planning a stair project — especially if you're working with tight spaces or unusual heights — try running your numbers through a calculator that includes automatic code checking. Enter your total rise, pick your calculation mode, choose your stringer type, and see if your design works before you buy lumber.

Try the stair calculator here and run your measurements through it with your real project constraints. See what the code warnings tell you, adjust your design if needed, then build with confidence.